From the winter 2021–2022 Sea Star print newsletter

Researchers use UW vessel logbooks to reconstruct historical groundfish populations

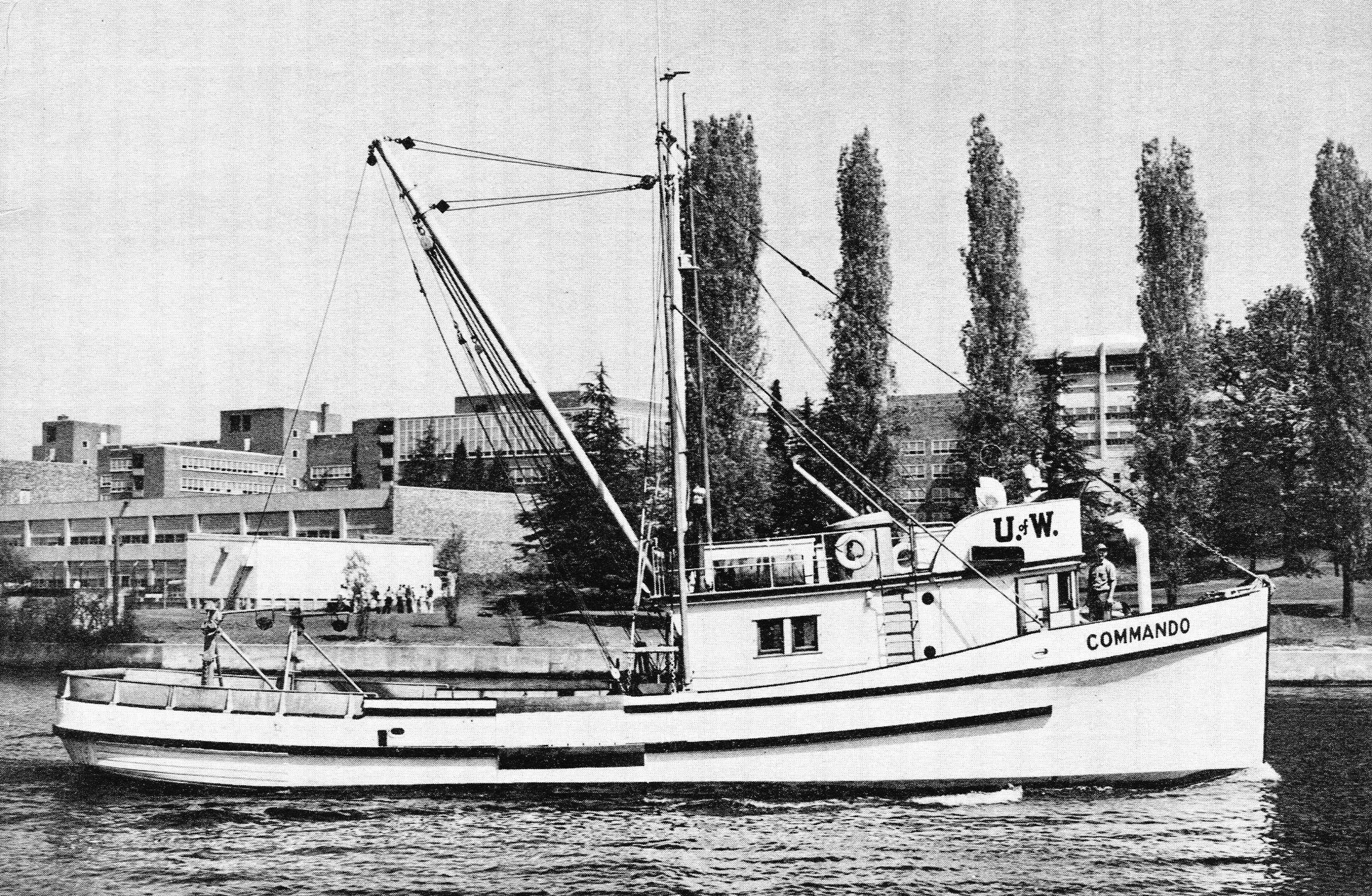

The R/V Commando passes through the Montlake Cut. Skipper Tom Oswold Jr. is on the flying bridge and engineer Olaf Rockness is on the bow. Photo: Bob Hitz

To understand how Puget Sound has changed, we first must understand how it used to be. Unlike most major estuaries in the U.S. — and despite the abundance of world-class oceanographic institutions in the area — long-term monitoring of Puget Sound fish populations did not exist until 1990. Filling in this missing information is essential to establishing a baseline that would provide context for the current status of the marine ecosystem, and could guide policymakers in setting more realistic ecosystem-based management recovery targets.

Researchers from the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, UW Puget Sound Institute, NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife have discovered an unconventional way to help fill in these gaps in data: using old vessel logbooks.

The crews of the University of Washington’s then School of Fisheries’ research vessels R/V Oncorhynchus (1947 to 1955) and R/V Commando (1955 to 1980), both of which were skippered by Tom Oswold, took notes on all of the fish tows conducted under their watch. With funding from Washington Sea Grant, the researchers combed through more than 1,000 of these logbook entries to analyze the information regarding the groundfish species caught in each tow, including when and where the fish were caught. Then, the researchers analyzed historical logbook data from 1948 to 1977 and contemporary monitoring data to reveal longer-term trends in the local groundfish populations. The research was published in Marine Ecology Progress Series last month.

Although there were changes throughout the periods analyzed, the researchers did not find that groundfish populations today in Puget Sound look fundamentally different from the historical populations.

“We see the same types of fluctuations in the historical data as in the contemporary data,” said Tim Essington, professor at the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences and the study’s lead author. “This suggests that boom and bust populations are natural, and speaks to the importance of having a long time view to establishing a baseline.”

However, some trends did stand out, Essington explained. For example, Pacific cod used to be very common but is rare today, and the abundance of Pacific spiny dogfish has decreased.

The fact that the researchers were able to fill in any of the historical gaps was really a matter of luck: the right people had maintained the research vessels at the right time.

“They were remarkable, the records,” Essington said. “They not only noted the species and size, but also detailed descriptions of the locations. It was amazing what we could reconstruct.”

A page from one of the logbooks on the R/V Commando. Photo: Bob Hitz

Bob Hitz was a graduate student at the School of Fisheries from 1957 to 1960, during which he ventured out on the Commando along with Oswold and his advisor, Allan DeLacy, to collect data for his research on Puget Sound rockfish. He remembers once being chastised for filling out the logbook incorrectly.

“I had misspelled one of the scientific names — that was the only time I remember that DeLacy got mad at me,” Hitz said. “He said that the logbooks had to be correct.”

This level of precision made Essington’s work possible decades later. For Hitz, the logbooks also became a rich repository of memories.

“When I was going through the logs of the Commando, I found an entry that I had written on May 3, 1960,” he wrote in a 2015 blog post. “It was for trip #6017 and it brought back a wave of memories, since that was my first encounter with the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. At the time I was being considered for a job with the Exploratory group which worked the outside waters from Mexico to the Bering Sea. The first thing that came to my mind was, would I become seasick once I was outside? If so, would three years of graduate school be wasted? There was no class about seasickness given at the [School of Fisheries], but there was talk.”

Although the researchers analyzed logbooks up until 1977, Essington explained that they became considerably less useful after 1973. As Hitz recalls, this was around the time the school began to place more emphasis on chartering the Commando for outside research, rather than using it for students’ education and research.

“I assume the logbooks became less important when the boat was being chartered,” Hitz said.

Essington described the project methods as “half detective work and half computer work.” The detective work involved the researchers carefully perusing the old logbooks while wearing N-95 masks to protect themselves from the mildew and dust (prior to COVID-19). The computer work involved analyzing how the catch rates of 15 groundfish species differed between the historical and contemporary datasets, to understand how the general groundfish populations differed between the two periods.

Given that the details within the logbooks petered out, and then stopped altogether once the Commando was retired, the researchers were forced to leave out an important period in their analysis.

“There was a 17-year gap between the captain’s books and current monitoring, and no amount of scrappiness could fill this in,” Essington said.

The years between the two datasets — the bulk of the 1970s and 80s — also happened to coincide with extensive environmental change in Puget Sound, including the implementation of regulations to address pollution and protect endangered species. A few changes particularly impacted groundfish: For example, the 1974 Boldt decision resulted in increased non-tribal recreational groundfish fishing. Subsequently, the introduction of bag limits, marine protected areas and species-take prohibitions in the late 1980s and early 1990s reduced the intensity of recreational groundfish fishing.

in June 2020, groundfish were added as a food web indicator species for the Puget Sound Partnership’s Puget Sound Vital Signs, which has guided policy since 2010. This research could help shed light on what to look for as healthy for this vital sign, the authors said.

“It might be better to think about baselines in the dynamic sense,” Essington said. “To focus on acceptable ranges of fluctuation, rather than a precise number.”

DEC

2021